- Home

- Yara Zgheib

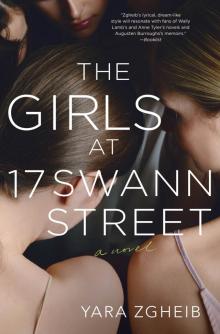

The Girls at 17 Swann Street Page 9

The Girls at 17 Swann Street Read online

Page 9

Even the dense, high-calorie supplement is offered in a choice of three flavors:

Vanilla, Chocolate, Pecan

Emm and I fill out the breakfast forms rapidly. Lunch and dinner prove more complicated.

Every lunch and dinner menu comprises three courses: an appetizer, a main dish, and a dessert. Two options are offered for each.

Again, circle A or B,

and Emm begins to fill hers. But I lag behind, frozen at the starting line: the very first appetizer on Monday.

Caesar salad with dressing and Parmesan cheese

OR

Basket of French fries

Parmesan cheese? Caesar dressing? French fries?

I skip the appetizer for now.

Perhaps the main course …

Fish fillet

OR

Mac and cheese

I am about to cry.

I know they look scary. Don’t let them overwhelm you. Let’s start with the first one,

Emm says.

I am so grateful. I look at her shakily:

You do not have to do this.

I know.

Her poker face is replaced with a smile. For a second.

Didn’t Valerie tell you the rules? It’s what we do.

Then she snaps back to business and the menu:

Caesar salad or fries?

Salad, I suppose, but before I circle it, Emm says:

A few rules first.

Number one: know yourself. I know the salad seems a safer choice, but if you aren’t willing to down a gallon of mayonnaise and eat every bit of cheese, then stick to the French fries.

I hesitate. Then circle the fries.

Next, the main course:

Be clear about your priorities, Anna: if you circle the fish, you must eat it. How committed are you to being a vegetarian? If you are, tough luck: mac and cheese.

But the cream! The cheese …

My voice gets caught in my throat. I am panicky, but Emm is firm:

Priorities.

Swallowing my tears, I circle the mac and cheese.

Now dessert:

Yogurt and granola

OR

Chocolate milkshake

What the hell, I have come this far. Chocolate milkshake it is.

Rule number three: don’t be a hero,

says Emm. I look at her, confused. She raises an eyebrow at me:

If you could really eat fries, mac and cheese, and a chocolate milkshake in one meal, you would not be in a treatment center, would you? Don’t bite off more than you can chew.

Literally.

One challenge at a time. Start with the fries. Next week, conquer the shake. Be kind to yourself; you have six meals a day and seven days of those to complete.

Six meals a day for seven days. I am exhausted after just the first lunch. But Emm nudges me forward and we make our way through them.

One circled option at a time. Other insight:

Be realistic. There is no “lighter” option in a place like this. The meals are planned and portioned so that all options are calorically equivalent. Everything will be scary and large. Everything will make you gain weight. So green beans or ice cream, choose what you are most likely to swallow, and maybe enjoy?

Which brings us to rule number five:

Use the resources you have, like the schedule. No high-volume lunch on oatmeal breakfast day. No saucy dishes before yoga; you do not want to have acid reflux in your downward-facing dog.

She then shares the biggest secret of all:

And if you really hit a wall, you can always strike the whole lunch or dinner out and opt for a sub meal.

A sub meal! That’s right! We have, at all times, three substitute meal options to choose from:

SUBSTITUTE MEAL A:

A ham and cheese sandwich, with pretzels, and yogurt and fruit.

SUBSTITUTE MEAL B:

A peanut butter and jelly sandwich, with pretzels, and yogurt and fruit.

And Sub Meal C, I discover, is what I was served for my first meal here:

A whole-wheat bagel with hummus, carrots, and yogurt and fruit.

You only get seven sub meals a week, though, so use them wisely,

Emm warns. But I am not listening, holding on to Sub Meal C with my sanity.

It had been a paralyzing first meal. A terrifying, cataclysmic experience. It had seemed impossible. It had not been. Now it seems like a dream.

The vegetarian option for lunch on Tuesday is a black bean burger. Sub Meal C.

For dinner: a cheesy baked potato, topped with sour cream. Sub Meal C. On to Wednesday, where the nonmeat option is a tomato basil flatbread. I could swallow that. Dinner, however, is spaghetti marinara. Cue my third Sub Meal C.

By the time I reach lunch on Friday, however, I have run out of sub meals.

Reevaluate your choices. This is not sustainable,

says Emm.

Why not? I protest.

The voice in my head argues desperately: Sub Meal C is a well-balanced meal! It contains fat, carbohydrates, vegetables, and protein. Reliably familiar and bland. If the purpose of food is nutrition for survival then I can just survive on that!

There! I have cured my anorexia on my fourth day at 17 Swann Street. But even I know it cannot be this simple. I turn to Emm for help. Emm?

But Emm is circling her own menu options, deliberately leaving me on my own. The rules are clear: Only seven sub meals. I try not to panic.

Most of the other girls have already finished and submitted their forms. The rest are nearly done. I look at the clock: I have four minutes left.

Animal crackers and cocoa to drink. If they can do this I can. I flip back to Tuesday’s menu and circle the black bean burger for lunch. I skip the baked potato that evening but select Wednesday night’s spaghetti. I race against the mounting anxiety. I reach Sunday. It reaches its peak.

Suddenly, it dissipates as I almost laugh out loud at my last dessert. My options are:

Apple crumble

OR

Animal crackers and chocolate pudding

I can take a hint. I make my selection and submit my menus immediately. Quick, before my brain catches on and I chicken out.

The nutritionist leaves with the forms and I realize what I have done. This week, I will be eating food. Not just any food: mac and cheese. And fries, a burger, spaghetti, chocolate pudding. This may be catastrophic.

Too late now; the forms are gone with the nutritionist. The girls move back to community space. I want to thank Emm for her help, but her spot is empty.

35

They had arrived early. Matthias checked in. They watched his suitcase roll away on the carpet; he would pick it up in the States.

He turned to Anna:

Breakfast?

Yes, breakfast. Always breakfast, her favorite meal of the day. Their last meal together until she followed him to America in a few weeks.

There had to be a Paul, somewhere. There was always a Paul somewhere. They found a Paul, she found a table while he pulled out his last coins. He did not have to ask her what she wanted: a pain au chocolat, and one for him. Deux cafés: allongé for her, crème with two sugars for him.

They had their last breakfast Chez Paul together in Charles de Gaulle Airport, Terminal 2E. Cream on his lip and his hand on her knee. She kissed both and finished the crumbs.

36

I remember that breakfast,

Matthias says, his hand on my knee.

Thursday evening, visiting hours. This time we are in my room.

I remember that breakfast too, just not how it tasted. I watch myself eating, licking, loving the pain au chocolat like watching myself on film.

Anorexia is not present in that memory; I could still eat and enjoy food. I could still recognize the texture of light, flaky pastry on my tongue. I could still savor good chocolate spread. Now that memory tastes bittersweet. Actually, it does not taste like anything. I have no taste buds anymore.

After years of

restriction, my brain, with effort, can identify three flavors: salt, sweet, and cotton. All three disagreeable, but cotton is the one I fear least. So I choose it every time, by default, to give my anxious mind some respite. Broth-based soups, green salads, popcorn, and apples. No pleasure but no pain at least.

I am told that some taste may be recovered after years of healthy, varied eating. The caveat being that that would require years of healthy, varied eating.

Well, I have my first week of that set. I tell Matthias about meal planning. He looks at me, incredulous:

You’ve got to be joking.

I feel the same way.

But tonight I also feel, perhaps prematurely, confident. I announce to Matthias:

When all this is over we’ll have breakfast, Chez Paul. Pains au chocolat and coffee.

But he does not take part in my reverie. He looks out at the magnolia tree.

Matthias, is something wrong?

Still looking out, he says:

No, Anna, nothing’s wrong. I am happy you listened to Emm.

But …

His hand leaves my knee and he speaks again, suddenly angry:

But I bought black bean burger patties for you, remember? Months ago! They’re in the freezer, right next to the frozen meals that do not contain dairy or meat.

I used to beg you to eat them! I even used to set them on the counter before work. All you had to do was put one in the microwave and press the button, Anna.

I did—

Don’t lie to me! I know you did not. I take the trash out every night, remember? You used to throw them away.

He had never confronted me. I cannot think of what to say.

And every time we went out I would order a basket of fries just in case, just in case you would eat one. One fry, Anna! Or one of my pizza crusts!

His voice is turning hoarse.

Our fridge is full of yogurt! We have cereal and oatmeal and toast! I used to beg you to eat! I used to fight you to eat!

We stopped fighting!

Yes! Because I gave up.

His hands to his face. After a while he runs them back into his brown hair. I used to do that. His breath escapes, jagged. He calms down and finally looks up.

His voice is quiet now:

I’m sorry, it doesn’t matter. I’m glad you listened to Emm. This is a big step for you, but I think you can do it. You will have good support next week. It’s just …

He looks out the window again. I want him to finish his thought. I reach for his hand:

Hey, you can say it.

He looks back without seeing me.

Just … why was I not enough?

I do not know.

Why Emm and not me, Anna? Why did we have to end up here? Why did it have to get to this for you to start to eat?

I do not know why I never touched his fries or why I threw out the food. I do not know why I lied every time he asked me about lunch. I do not know why I tried to starve myself and why I am eating now.

I have no choice here but to eat; they took my freedom away. You loved me too much to do that—

I nearly killed you,

Matthias interrupts.

His jawline is taut and a vessel is pulsing madly at the base of his neck. His hands are in fists. I hesitate before touching them lightly:

Hey …

Sobs. His and mine. In Patient Bedroom 5 of a horrible place called 17 Swann Street.

You brought me here. You saved my life,

I tell Matthias, still crying. I am sorry,

I am so sorry. I do not know why or how it got to this.

I don’t know why either,

he whispers,

but I’m here.

I am here too,

I promise. And to keep fighting this.

We hear Direct Care’s heavy footsteps and panting come up the stairs. Visiting hours are almost over. Matthias stands up.

Noses blown, eyes dry now, he asks:

When all this is over, Chez Paul?

I swallow my saliva and fear:

Pains au chocolat and coffee.

He leaves me at 17 Swann Street with my evening snack and myself. And a week’s worth of food to swallow that I have not tasted in years. I do not have to remember or like them, I just have to try. I just have to chew and swallow, chew and swallow, one cotton bite at a time.

37

Sunday. I have been here a week, and to my surprise, am not dead. I lie in bed, relishing the first few minutes and rays of the morning.

I reflect on my first week at 17 Swann Street. The psychiatrist had said that I was depressed and my brain was hungry and irrational. Hungry Brain Syndrome: the reason I was constantly cold, sad, tired, paranoid, angry.

The nutritionist had said that I was undernourished and that I had to eat. Dairy, and oil and grains and beans and tofu and nuts and granola and eggs. She had even suggested junk food. She was mad.

The therapist had said I repressed my feelings. I had explained I have none. Unless she counted feeling cold, and tired, and empty, and sad. I had explained I have no energy for superfluous things like feelings. What little food I ate I used to survive; no leftovers for hormones or tear glands.

Are you happy?

she had asked.

I had shrugged.

Angry?

Shrug.

Are you sad?

Shrug.

What do you feel like doing?

When?

Today, tomorrow, with your life?

Her questions had felt tiresome and irrelevant.

Do you feel hopeless?

I had cried.

My diagnosis was anorexia nervosa. My insurance had agreed and had authorized my stay here till I was restored to a healthy weight. The primary care physician had examined my test results, and was concerned with my heart, brain, stomach, kidney, pancreas, liver, bones. Just those. But she had not addressed my dormant ovaries, so I had brought them up.

I had told her I could not remember the last time I had a period. A few months, perhaps years ago. But I did want a baby, so could she please tell me:

When will my periods return?

She had not replied.

I had completed three meals and three snacks every day of this week. None had been popcorn or fruit. I roll onto my stomach in my one-person bed and breathe into the pillow. Hello Sunday.

I am not particularly religious, but I had asked for a church pass. My treatment team had promptly endorsed this spiritual supplement to my nourishment. All I had to do, I was informed, was get through breakfast and a snack, and Direct Care would drive me to mass at 10:30 A.M. I could do that.

So, after the midmorning snack, Direct Care hands me my phone. Then she, I, and one of the other girls step out into the parking lot.

The girl’s name is Sarah. She had come in on Friday. Exceptionally; patients usually come in on Mondays but, as Emm had explained,

The weekender’s bed was free.

On the day she had arrived at 17 Swann Street, her hair was the first thing I had noticed. Fiery, and it matched her lipstick, I had noted with envy. I own three tubes of red lipstick myself, but I am too vanilla to wear them. I watch Sarah wear hers, her hair, and her Southern drawl with showstopping confidence.

Today she is also wearing a long flower-print dress and a pair of Marilyn sunglasses. She sways toward the service van sensually. My blue jeans and hair in a bun follow. We climb in the back. Door shut.

Direct Care starts the engine and we drive off to church. I do not anticipate the rush of emotion that follows.

It fills my lungs suddenly as the van backs out then turns right on the street. From my bedroom window on the east side of the house where I have been for a week, I could only see as far as the curb. Now it is behind us. Now I watch the houses and gardens roll by, not realizing just how trapped I had felt until a tightness in my throat disappears.

The drive is short. The church is an unremarkable building five minutes away. There is a w

ide parking lot on its right, a green field on its left, so green against the spotless blue sky, I want to lie in it. We are dropped off and told we will be picked up in an hour, at this precise spot. Then the service van leaves us, stunned and free, and slightly disconcerted on the sidewalk.

For a moment Sarah and I just look at each other. We do not know what to do with ourselves. We have an hour to blend in as normal churchgoers, but how does one do that? Surely someone is going to recognize us: runaways from that house. The one where they keep the girls who cannot eat. We walk to the entrance hesitantly.

So far so good, until … we are stopped, by a well-meaning matron and a heaping tray of hot coffee and doughnuts. Sarah and I freeze, but only for a second. We then politely refuse and walk on, smiling at each other furtively. Blending in, blending in.

The big hall is lined with stained-glass windows, colored light pouring in. The ceiling high enough that from it could easily hang a trapeze. We slip quietly into the last pew just as the choir begins to sing. It is glorious. Music. It drowns out everything: the psychiatrist, the nutritionist, the therapist, Direct Care, my family, Matthias, the sadness, the anxiety, the fear. Every muscle in my body feels like it is unclenching. I can breathe. I do. I could be in a mosque, a synagogue, a temple. I could be on a mountaintop.

I do not know if anyone hears prayers. I decide to pray anyway. I let my shoulders slouch, my back bend, my ankles uncross, and myself be completely honest.

I am not depressed. I am sad, because I am away from those I love and every day without them is a day lost. Because I lost a brother and a mother and know what a day lost means.

I am not undernourished. I am starved for a meal I would not have to eat alone. For someone to love me and tell me that I am more than enough, as I am.

The Girls at 17 Swann Street

The Girls at 17 Swann Street